More research is NOT needed

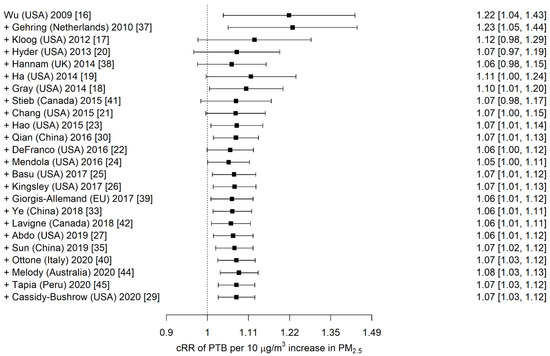

“More research is needed” has become a common scientific cliché. It is difficult to think of any situation for which more research is not needed. All scientific findings require replication, either in a controlled environment or in other settings and sub-populations. Ideally, studies should also be repeated by independent research teams or investigators to improve credibility. But when do we stop? Surprisingly, there is a dearth of methods to help us decide when not to undertake a study. Unsurprisingly, this has led to considerable research waste. The studies that provide the strongest level of observational evidence - systematic reviews and meta-analyses - have unwittingly contributed to research waste. China, the US and the UK are the largest contributors to the boom in studies that involve research syntheses. Compared to primary studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses can potentially motivate, and therefore accelerate, the production of wasted research. Such studies tend to conclude with the same cliché - “more research is needed”, “Further research is needed” or its variants. Unlike primary studies, these studies justify the cliché based on the level of heterogeneity between the studies. Inconsistent findings from systematic reviews and observational studies have motivated researchers to conduct more studies, but some degree of study heterogeneity is inevitable. The consequence of this feedback is a burgeoning research effort that results in marginal gains. It remains unclear as to whether a new study is needed to establish that an adverse association exists (sufficiency) and whether a new study is likely to change the aggregate evidence to date (stability). Our team developed a method using cumulative meta-analyses to ascertain the sufficiency and stability of observational associations and demonstrated the value of the method for assessment of the association between preterm birth and fine particulate matter air pollution (PM2.5). We found that Preterm birth is associated with elevated exposure to PM2.5, and it is highly unlikely that any new observational study will alter this conclusion. The mathematical detail on our derivation of a stability threshold can be found in the reference below. However, the concept of the stability threshold can be gauged from an inspection of the following forest plot of the cumulative meta-analysis of the studies, sorted in chronological order of publication year. It is visually evident from the forest plot that the cumulative observational evidence has not changed since 2015. Our stability threshold quantifies the extent to which a new study would need to change our conclusion. We found that for this to happen, a new study would have to observe that higher particulate pollution exposure reduces risk of preterm birth and to demonstrate this protective effect convincingly (with low variance), which is very unlikely. Do we need more observational studies on this topic? Perhaps. We still need to better estimate risk, particularly in sub-populations. Do we need more observational studies to demonstrate that this exposure is harmful? No.

References

- Pereira, G. A Simple Method to Establish Sufficiency and Stability in Meta-Analyses: With Application to Fine Particulate Matter Air Pollution and Preterm Birth. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2036.

- Fontelo, P., Liu, F. A review of recent publication trends from top publishing countries. Syst Rev 7, 147 (2018)